Ever wonder how I write posts on this blog (and the one that preceded it), articles in magazines/journals, and/or more specialized projects?

I’m guessing not.

I’m just one little bay/strait/channel in a giant ocean of text. I try to remember that.

If you are curious, you’re not alone. I’ve periodically gotten questions about how I come up with, outline, and implement ideas that I haven’t been able to answer very well. 1 In fairness, I generally don’t devote too much thought to it. Recently, I acquired unexpected motivation for introspection. 2

I’m going to start a series about my creative process. This first post focuses on the odd way I believe my mind has adapted itself to organize information.

Talking in blocks

The storytelling game

Have you ever tried to tell a story that randomly mutates into something totally unrecognizable?

Stories have always been very important to me. I was hearing and telling stories from a very young age. My parents would make up stories to entertain me when I got bored. I learned how to dictate my own stories for them before I actually learned the rudiments of written English composition.

In elementary school, I played collaborative turn-based storytelling games with my childhood best friend. I would start the story, then he would take a turn telling a segment, and I’d tell a segment during my turn.

It was highly improvised, to put it mildly. We never had any conversations beforehand about basic parameters and never planned about where the story would go. Nothing was ever written down. Stories could only be told during lunch breaks, carpooling, and the occasional weekend hangout.

No story was ever told continuously for longer than a couple days. After that, we started over. Nor was the process totally cooperative. My friend could and often did unpredictably change the story’s direction at any arbitrary time. Stories degenerated into indirect struggles for narrative control.

Sometimes we’d invite some other friends to join us and the two-person game would become the far more chaotic group turn-taking story game.

I needed to direct the story just enough but not too much. If I got too fixated on getting the overall story I wanted to tell, I’d always be disappointed. It would get too messy and convoluted if I didn’t assert myself at all.

It would be easier if I had devoted more thought to the overall narrative arc of the story and how I’d keep my friend(s) from digressing. I rarely if ever did. I was very young and simply lacked the intellectual means to plan anything that complicated. So I had no idea how the story would end either and anything beyond the immediate future was too dark to make out.

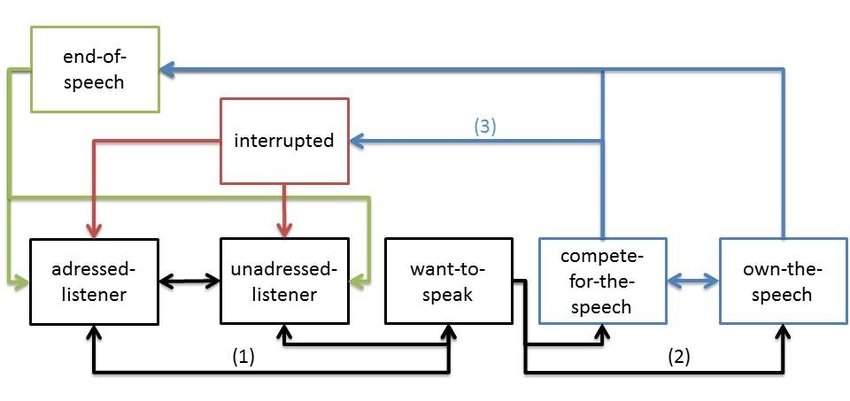

The amount of story I could feasibly imagine at any time was a small linked collection of segments. I held them in my head at once. Every time a friend injected a wildcard I had to discard some segments, invent replacements, and re-arrange the segment organization. I’m going to interrupt my own retelling of the storytelling game to point out the basic issues:

- Segments are non-contiguous: You are always interrupted by the counterparty’s turn, and you will eventually be interrupted by lunch break (or whatever else) ending. Context must be stored in short-term and long-term memory in between turns and game sessions. External storage is not permitted.

- Segments are frequently disrupted: You must have a logically resilient organizational schema that adapts to one or more people frequently interrupting and diverting the flow of conversation and the structure of the overall narrative. This also must be held in short-term and long-term memory.

- Segments are organized by children: You are not a master storyteller with decades of experience and an extensive fiction library. You are an precocious yet immature child with an underdeveloped brain. You are not yet able to organize complex information in writing and you must do so in an oral storytelling game played under Calvinball rules.

Unfortunately for future friends and romantic partners, years of playing the storytelling game and coping with similar challenges eventually paid off.

The paragraph game

They call it “talking in paragraphs.”

It’s a bad habit that I have struggled in vain to curb. If you’re close to me, you’ve probably accepted on some level that I’m always going to do it and the most you can ask of me is to do it less.

I got the image below from the TVTropes “wall of text” entry. At my worst, that’s what talking to me can be like.

I launch into a monologue, ignore any interjections into the conversation, and resume where I left off after someone else breaks up my uninterrupted flow of speech. I continue talking until I’m finished or someone forces me to stop.

I launch into a monologue, ignore any interjections into the conversation, and resume where I left off after someone else breaks up my uninterrupted flow of speech. I continue talking until I’m finished or someone forces me to stop.

Person: “Can’t you just write this down later?”

Me: “Actually…nope. Sorry!”

Person: “Can you at least tell me how much longer until you’re done?”

Me: “You’re not going to like the answer to that one either, buddy.”

I am usually so transfixed by the need to finish what I have started that I sometimes do not even hear other people talking to me.

If someone successfully interrupts, I single-mindedly try to return back to where I was stopped as soon as they stop talking. When I don’t exercise much self-control, I can become irritable or even upset if I cannot finish the entire sequence I have projected forward in my mind.

Setting aside how annoying this can be for others, I’ve come to appreciate being able to do it. I don’t think it really amounts to talking in paragraphs. It’s more like talking in blocks.

I instantly generate a linear sequence of conceptual blocks that are then automatically converted into coherent speech. The logical block organization resists progressively less polite attempts to change the subject or interject different points of view. Block organization is organized internally the entire time without any external storage.

Certainly it helps to have read and thought a great deal about the subjects I’m lecturing about. That pre-organizes the blocks and reduces the amount of online processing I’m doing. However, I still am able to talk in blocks about topics — like interpersonal events — that aren’t as well-structured as nonfiction books.

Don’t try this at home

In school, they teach you how to use notes, outlines, index cards, diagrams, and similar tools to offload mental organization onto external media. In an ideal world, everyone should do that. It really helps. But what if that doesn’t really work for you?

Then you’ll need to be like me.

I’m not totally incapable of outlining. I’ve trained myself how to do it decently well. When a project is sizable, complicated, and/or important, I will outline because I have no other choice.

It’s just that for everything else, I find it slow, bothersome, and often ineffective. I’ve already mentioned my problems with organizational tools in a previous post.

What you’re reading right now was generated without any outlining whatsoever. If I had tried to write it guided by an outline or a mind map, it would be far more difficult for me to translate the inner organization I came up with to a formal representation.

I’m sometimes angry at the younger me that played too many rounds of the storytelling game. That little brat made life much harder. If I’m trying to manage a technical problem, I instinctively outline before I do anything. Why is that so hard for other stuff?

I guess it doesn’t matter. I’m stuck with the alternative regardless. I heavily rely on internal mental structures to organize information to get the benefits everyone else gets from outlining and similar means of external organization. It works more often than it really should, but I wouldn’t recommend you imitate me.

What I never bothered to think about until quite recently was how and why it works so well for me. I have an informal hypothesis about that, but you’ll have to stick around until the end to hear it.

I repeat, don’t try this at home

When in doubt, “roll tape!”

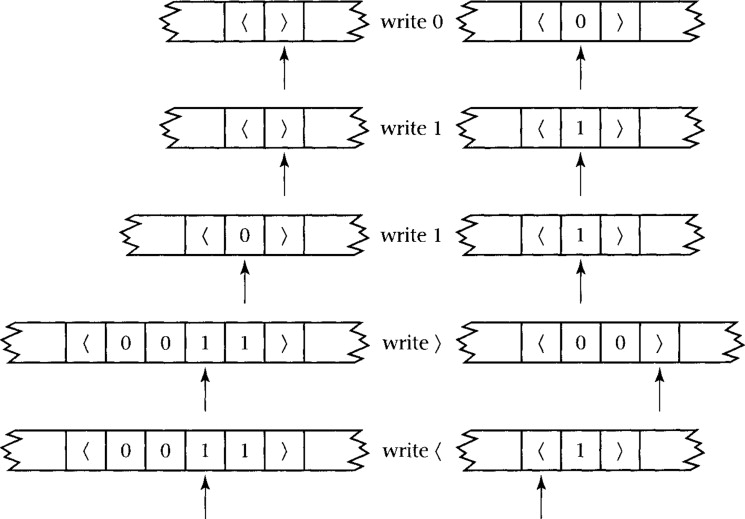

Imagine, if you will, a sequential storage format resembling rolls of tape. That tape might store audovisual media (film reel, VHS, DAT, betamax, what have you). It could also be magnetic tape used for bulk data archiving. Or it could be whatever other tape you want to think about.

It really doesn’t matter, just go with the tape you can visualize best. There’s lots of cool-looking pictures of tape-like data structures and I found one to aid your immersion.

Suppose there’s a movie stored on the tape. For the sake of argument, assume that you can’t use a media device to play the tape. You’ve come to an unfortunate fate and have to play it directly in your head using some mysterious power.

You cannot focus your attention on everything on the tape at once. However, you at least have:

- A gestalt sense of what the overall sequential structure stored on the tape consists of.

- The ability to hold in focus both your current position on the tape and at least whatever is somewhat ahead and/or somewhat behind it.

If you are physically healthy, in a good mood, and have enough free time, you can “play” everything on the tape in sequence. You incrementally play every part of the movie by relying on your prediction of what you can clearly see ahead of where you are in the movie and your crude overall understanding of how it ought to fit with the entire media stored on the tape.

I know this may sound like a strange and convoluted metaphor, but this is what writing feels like to me in the best case scenario. I have a crystallized structure in my head, and I can sit down and write automatically for hours without stopping. I only need the gestalt picture and a means of vividly simulating the area immediately ahead of where I’m currently writing.

I defer fleshing out something until it is absolutely necessary and barrel through the entire mental outline until I’m done. I can keep improvising with just enough idea of how it should fit in with the overarching structure to come out with something that at least can be a basic first draft. But that’s the best-case scenario rather than the average-case scenario.

Catastrophic forgetting

All of this tape business is well and good, but what happens if I run out of time and energy? Not having a real outline now becomes a very big problem. I might lose the entire inner organization I’ve constructed and even my prediction of what I ought to write somewhat ahead of where I stopped. There isn’t any guarantee either inner idea gets stored in long-term memory. It could be gone tomorrow or even gone in several hours.

I’ve lost good ideas too many times, so I developed fallback methods in case I run out of juice or have to stop for a while.

- Deliberate mental rehearsal as a fallback if I can’t write anything outline-like down.

- Writing a small note-to-self snippet down and hoping that when I come back to the snippet I’ll be able to retrieve enough associated context to pick up where I left off.

- Talking about my idea if I’m with someone else that’s willing to listen and seeing if that makes it easier for me to remember it.

- Posting about it on social media and then trying to use that to force retrieval if anything is stored.

- Leaving some associated artifact, like a picture I found on Google Images that reminds me of what I was talking about, in the same folder.

- If it gets too late and I need to go to sleep, trying to force myself to dream about whatever I was writing about before I went to bed.

- Thinking about another subject in the same broad subject area and hoping it’ll make storage and retrieval of my idea more probable.

- Writing something down in a physical notebook and hope my very poor handwriting won’t get in the way.

That isn’t every single fallback trick I use, but it’s enough to suggest what the others might be. The good news is that I’m getting better and better at storing and retrieving my ideas without needing to write much of them down. My skill at doing this seems to be increasing rather than decreasing with age. Cumulative practice and writing about the same roughly overlapping subjects over and over again helps. But neither are enough on their own.

When optimistic assumptions fail

The other dubious assumption of the “tape” scenario is that I have a logically sound overall structure in my mind when I begin writing. It certainly always feels like I do — otherwise I wouldn’t be writing it — but feelings can be misleading.

I can generate drafts and then realize midway through that the structure isn’t good and I’m rambling about nonsense. The order of the overall idea might need to be re-arranged and much of what I’ve already written could get cut. At worst, I may need to radically rethink the entire thing to avoid scrapping it altogether.

Even a good first draft may just be deferring the inevitable realization that I need to make dramatic changes. I have much looser editing standards for blog posts than I do for everything else, but I still can run into trouble. Having a coherent structure isn’t the only big assumption. Having a firm structure at all is a much bigger one.

The structure isn’t always all that crystallized at the outset either. I might go into a draft with a vague and fluid idea of what I’m going to do and trying to write something crystallizes my mental outline from the bottom up. I’ll move things around and try different approaches until I start seeing results.

I haven’t said anything whatsoever about where the structure comes from to begin with. It doesn’t just emerge from the mystical aether, right? I don’t really understand many other aspects of my imagination very well, but I do have a good idea of where the components of the structure for any given writing outline come from.

Rotating shapes into words

Shapes and words

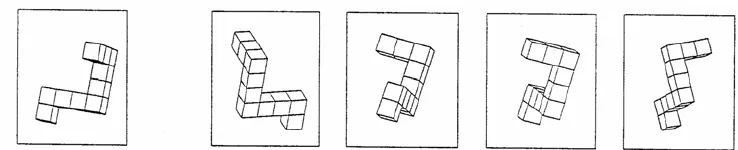

Believe or not, I come up with things like the post you’re reading right now the same way some of you might solve math and physics problems. I’ve always found the “shape rotator vs wordcel” meme silly. But after much introspection I’ve come to the odd realization that shape rotating (or something like it) is literally the source of every single nontrivial agglomeration of written words I’ve ever produced.

This strange realization became blindingly clear to me after I went back and revisited Roon’s blog post about the discursive demon he accidentally spawned:

It turns out that when you give a large set of people a battery of cognitive tests and run their scores through some statistical magic, two principal component axes emerge: visuospatial and verbal intelligence. Scores on both sets of tasks are still positively correlated (being good at one makes you more likely to be good at the other) but they display the largest orthogonality of cognitive ability. The most tangible, common, and yet inherently funny way to detect visuospatial skill are mental puzzles that ask you to envision which of these compound shapes on the right match the one on the left, albeit rotated:

Most if not all of my ideas begin in my head as imagined physical objects.

At first glance, there’s little novel about that. Everything we “see” when we read literary fiction, for example, is constructed with some degree of vividness by generative rules specified in the prose. If a character is said to be “gaunt”, “furtive”, and “shambling” you’re already well on your way to “visualizing” an animate entity with attributes and behaviors. So what’s new here?

Shake it, rotate it

For me, every idea I come up with is rendered as something crudely approximating a manipulatable three-dimensional physical object. 3 Depending on how vividly I imagine them, these objects can have texture, mass, volume, and even force and velocity. The only things I have never imagined are color, smell, touch, sound, and taste. It is not unusual for them to have moving mechanical parts. If the objects move, they usually do sequentially but it is not impossible for them to move concurrently or in parallel.

Multiple idea-objects can be linked together in spatial, logical, causal, and temporal relationships and patterns. Hierarchy and recursion are just two of many possible examples. The formal properties of the impressionistic visuospatial objects often precede everything else I imagine about them. The objects are repeatedly examined from different perspectives in what seems…I guess…to be something like mental rotation.

For any of these objects to become useful, they must interact with at least three other imagined factors:

- Semantic content, e.g what does the idea-object mean?

- The hypothetical physical appearance of the idea-object(s) as text on a digital screen.

- Aesthetic qualities and ideals of the idea-object that appeal to me.

The strength and desirability of an idea to me increases the more seamlessly the formal properties map into, feed into, and/or flow into items 1-3. When something feels overwhelmingly strong and desirable, I start to think about how I might write about it. That feeling of “I am compelled by this object” alone isn’t enough, I need an actual point to make.

The mapping/feeding/flowing is, though, the driving element behind my motivation to think through what I’m interested in talking about. How that happens and how it relates to the way the mental outline structure emerges is something I’m much less sure about and can’t really describe that well. What I do feel increasingly certain about is that any internal outline I come up with depends on my basic capacity to think about ideas and concepts visuospatially.

Another One Weird Trick

Before you ask…the fact that I tend to perceive ideas I’m interested in as physical objects doesn’t mean I’m that good at describing their visual and physical features verbally or drawing them on a sheet of paper. Even when I write in great detail about something I know very well, I still intuitively feel like all I’ve done is produce a debased imitation of a transcendent quasi-platonic form. However, that’s good enough for me.

After all, I’m writing this post on a mechanical keyboard instead of painting it on a canvas. If I was really into making visual art, I might not enjoy words as much as I do. I’m really lucky to have such strong visual/physical perception of ideas that often don’t really have any inherent visuospatial representation. If I didn’t, I’d probably be screwed. Even training myself to write down outlines instead of winging it probably depends on the baseline visuospatial representation I’m describing.

I sometimes struggle to explain to others why I find some things so intuitively appealing and fascinating because I can’t verbalize my visuospatial perception of my objects of intellectual fixation. I’m not sure how common my way of perceiving those objects is, and I have no way of knowing if other people who are similar to me have similar physical representations too. I do know that it’s hard for me to really be passionate about something unless it feels physically pleasing to me inside.

I’ve got an naive theory that perceiving ideas and concepts as visual/physical things is what helps me keep so much in my head at a time. It also probably aids in retrieving things I might otherwise forget, starting up again after I’m interrupted, and being able to improvise so much in both writing and speaking about complex topics. It’s not that I’ve never thought about it before, it’s just that I never thoroughly examined how I imagine things as a whole up until now.

I’d like to learn more about how I might be doing all of this, and there’s a stack of cognitive psychology papers and books on imagination, simulation, and representation that I need to finish reading at some point.

Until next time

That’s it for now. This post was incredibly long because I need to ground everything afterwards in a solid understanding of how I think my imagination works. What I’m going to relate next might not make sense without that prior understanding. I could be wrong — introspection is not all that reliable — but it’s the best I can do with the knowledge I have.

In my next post, I’ll talk more in detail about how the imaginative process I just talked about in so much exhaustive detail actually congeals into writing and give a worked example. The final post in the series will explain what you might and might not be able to practically get out of learning about how I think and write.

Footnotes

-

Admittedly a good deal of it simply comes from other people. An editor might send me a message asking me if I could write about X or Y. A client outlines something of interest I could do for them. Project team members or creative collaborators exchange ideas with me. Someone I know is putting together a conference and I get the parameters from them. The vast majority of my ideas, however, are a byproduct of a peculiar creative process I have intuitively developed and refined over time. ↩

-

I’ve been trying to help someone I know get started with their writing. Since I did partly learn to write nonfiction by unconsciously reverse-engineering how other people did it, I figured I could provide some insight simply by going into the nature of how I get ideas out of my head and develop them. This post began as an informal guide I was writing for them. I’m opening it up to everyone in the hope that it can be helpful to a broader audience. ↩

-

If I were to hazard a guess, the “3D” here is often like the unique perspective used in the Wolfenstein, Doom, and Duke Nukem games. Doom, for example, appears to render 3D space but projects from a 2D floor plan. Other analogies that come to mind are vector graphics and rotoscoping. The “resolution” is, as you may surmise, highly variable. ↩